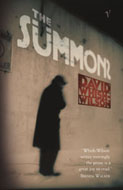

The Mary Smokes Boys – Patrick Holland, Transit Lounge, 2010

Patrick Holland’s terrific second novel The Mary Smokes Boys begins with its main character, a ten year old Grey North watching fireworks flame up into the sky, the sights of children his own age enjoying rides at an exhibition fairground seen from his position at a hospital window, having just found out that his mother has died giving birth to his new sister, Irene.

The opposition between the carnival festivity and Grey’s sombre mood is deliberate, and suggests the social position that he and his family occupy in the town of Mary Smokes – just an hour away from the lights of Brisbane but another world entirely, reached by passing through the city’s ‘industrial western outskirts. Neglected parks. Commuter tract wastelands. Concrete brothels bearing names of flowers in neon – Tiger Lily, Lotus, Sakura. Colossal empty shopping centres whose monotonous geometry invited vandalism. Wisps of juvenile gangs at the edges of shadows and inside dim culverts…Then came the family’s home in the Brisbane Valley. Mary Smokes was a town surrounded by blowing fields. In the west was a broad corridor of flatland before the Great Dividing Range before immense inland plains…The wide and empty country in which the world was uninterested.’

Grey’s father William is a manual labourer, and a drinker. When they retire to their home in Mary Smokes it is upon Grey’s shoulders that the task of raising his sister primarily falls. While Grey’s mother was alive, he had remained close by her, the object of his adoration and love. His mother had married badly, the result of a teenage pregnancy of which Grey is the fruit. His mother is a wonderful character, even though we see her entirely through Grey’s eyes. Just like the young female character in Chris Womersley’s equally terrific Bereft, Irene Finnain is linked closely to the land, and despite the Catholic piety which consoles her, we also get the strong sense that she takes an equal comfort in an apprehension of the mystery of country, whose spirit or essential nature she seems closer to because of the Irish language that she speaks, but which Grey never bothers to learn (indeed, Grey’s best friend Eccleston, a ‘half-caste’ Aborigine is similarly bereft due to the loss of his mother’s language, as it relates to the mystic connection to country that he senses, but does not entirely apprehend in the way that his ancestors did.) Irene Finnain’s consolations ‘were her son and prayer, and walks on car tracks over the plain or on foot tracks she made herself through woodland. She collected wild flowering herbs in the rock outcrops that grew in the shade of the big gums, she sits on fallen trees and watches ‘the wind turning over the dry understory leaves one by one…’

After Grey’s mother’s death, however, Grey becomes one of the town’s Lost Boys, taking to the night with his friends to walk, and drink, and observe. Although the novel is set just outside of Brisbane, because much of the novel is set at night, the atmosphere is by turns haunting and menacing, the style is at once spare but lyrical when necessary, the tone is biblical and somewhat reminiscent of early McCarthy, while a darker palette is used to characterise the Lost Boys and their muted conversations over a campfire at night, with the land itself a powerful presence. Holland’s descriptions of the land and the weather that passes through the town are particularly beautiful, as a reflection of the emotions of the characters. Much time is spent simply sitting and watching, a reminder of the static nature of the lives of the characters as they recapitulate the mistakes of their forebears, and all of the characters appear to carry with them the unspoken burden of a grief and a guilt for things that they have not done, even as the nature of their environment is subtly altered by their presence on the land. The boys and Grey’s sister Irene in particular are beautifully drawn, with humour and great pathos. In the absence of adult models the Lost Boys and Irene draw their strength and lore from the land that they traverse, and the waters that pass through the land. The bonds between the youthful characters are intense and their actions are never predictable. They are loyal to a vision of friendship as family that endures despite the passing of years and the mobile nature of the limited employment available to them. But even as they leave and return, and age and love and lose hope, always there is the Mary Smokes Creek, in flood or broken into pools, and their observance of the rituals of their ‘lost’ childhood, the sense that the land and their observance of the simply observed rituals of watching, and sitting beside the creek at night, both defines them and confers upon them a sense of identity, and belonging, a communal expression of both the sacredness of the land and their friendship:

‘So the town’s wild boys made some of their ocean of time significant. At Mary Smokes Creek…The water’s violence had grown quiet, stored like the violence of a candle flame…Slabs of granite and basalt were settled in the bed and the water purled around them, though in time of heavy flood you heard the rocks grinding, the water turning them over…And all this, that they barely comprehended themselves, was the boys’ secret at this hour of the night. No-one else in the universe was watching these waters. The boys and god were alone. Grey imagined they were the water’s keepers.’

The Mary Smokes Boys works patiently and skilfully towards its dramatic and violent conclusion. It has deservedly just been long-listed for the 2011 Miles Franklin award.

The Mary Smokes Boys – Patrick Holland, Transit Lounge, 2010. From the dustjacket – ‘Grey’s mother dies giving birth to his sister Irene and the tragedy haunts his life in the small town of Mary Smokes. Grey prays that his mother will be returned to him in some form, so he might protect her from the world as his father did not. This prayer, Grey believes is answered in his sister Irene. He becomes obsessed with protecting her purity and innocence…’